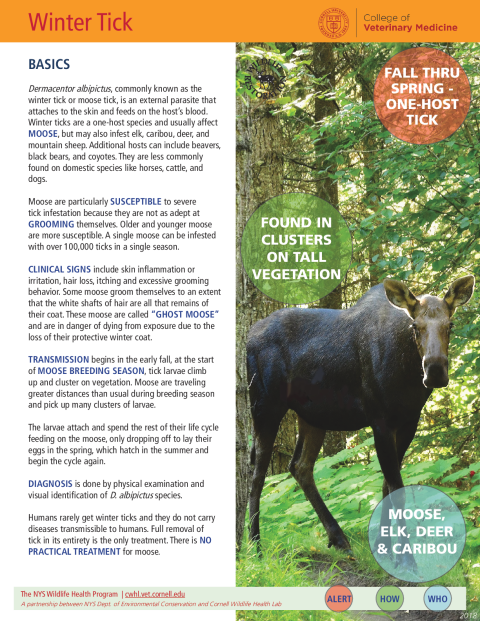

Dermacentor albipictus, commonly known as the winter tick or moose tick, is an external parasite that attaches to the skin and feeds on the host’s blood. Winter ticks are a one-host species and usually affect moose, but may also infest elk, caribou, deer, and mountain sheep. Additional hosts can include beavers, black bears, and coyotes. They are less commonly found on domestic species like horses, cattle, and dogs.

Moose are particularly susceptible to severe tick infestation because they are not as adept at grooming themselves. Older and younger moose are more susceptible. A single moose can be infested with over 100,000 ticks in a single season.

Clinical signs include skin inflammation or irritation, hair loss, itching, and excessive grooming behavior. Some moose groom themselves to the extent that the white shafts of hair are all that remains of their coat. These moose are called “ghost moose” and are in danger of dying from exposure due to the loss of their protective winter coat.

Transmission begins in the early fall at the start of moose breeding season, tick larvae climb up and cluster on vegetation. Moose travel greater distances than usual during the breeding season and pick up many clusters of larvae. The larvae attach and spend the rest of their life cycle feeding on the moose, only dropping off to lay their eggs in the spring, which hatch in the summer and begin the cycle again.

Diagnosis is done by physical examination and visual identification of D. albipictus species.

Humans rarely get winter ticks and they do not carry diseases transmissible to humans. Full removal of a tick in its entirety is the only treatment. There is no practical treatment for moose.